Previously: Today’s memo is brought to you by Caplight.Caplight puts VC data and deal flow in one place. The best venture investors in the world use Caplight to track private company valuations and fundraising activity, and to trade the private markets. Book a demo here. Ask your dad about Mosaic. The Internet as we know it did not exist in 1992. It was a niche system for academics with an ugly interface. To access the web, you needed to be a technically savvy engineer. There were roughly twenty sites up across the entire Internet that year. If you did not work at a university, government lab, or tech company, you did not have access. The Internet in 1992 was entirely uncolonized like the Americas in 1492. Marc Andreessen was a kid from the midwest studying at UIUC. In 1993, he launched Mosaic, the first successful Internet browser. It integrated multimedia - text and visuals - to create a much improved user interface. It also worked on both Windows and Macintosh operating systems, an impressive feat. Mosaic was so impressive that it compelled Jim Clark to reach out to Marc and offer him a job. Jim Clark was the founder of Silicon Graphics and he was looking to start his next company. He took Marc Andreessen under his wings and they decided to build Mosaic on steroids. At the time, Mosaic was going viral, with around a million users in just one year. The consensus view, however, was that the Internet was not commercial. No one thought it was a place to make money or win consumers. Jim and Marc wanted to prove the world wrong. So Jim invested $3M to hire Marc’s friends. They would call their company Netscape. There were originally two products: a web browser and a web server. The plan was to give the web browser away for free and then make money on the server. To Netscape’s dismay, a competitor, Apache, was intent on making servers for free. That meant Netscape had to work twice as hard and four times as fast. The young coders made a habit of binge drinking Coke and sleeping in the office. The first Netscape browser was released in October 1994. It was revolutionary; Netscape’s interface was the browser equivalent of an iPhone. It was so good that Marc and the guys decided to backpedal on their “free” pricing. Netscape allowed consumers to use it freely, but started charging businesses for use. Revenue grew exponentially from their enterprise browser sales. Everyone on the Internet was using Netscape. Clark and Andreessen beat Microsoft to the browser game. If it were up to Bill Gates, every man, woman and child would pay a fee to download browsers. On August 6th, 1995, Netscape went public at a valuation just over $1B. There was so much demand, Netscape closed the first trading day worth $3B. Jim Clark was worth $663M afterwards. Unfortunately, Microsoft was watching and waiting. A few weeks after the Netscape IPO, Microsoft launched Internet Explorer. They also bundled it into their Windows 95 pack for free. The rest is history. It became obvious Netscape couldn’t compete with Microsoft. In 1998, AOL bought Netscape for $4.2B in an all stock deal. Ben Horowitz had been working with Marc Andreessen as a product manager at Netscape. After the company got acquired by AOL, he stayed on as a VP in the eCommerce division. A year later, he founded a company called Loudcloud. Loudcloud was a cloud computing company. They provided cloud infrastructure for software businesses. Marc was Ben’s first investor and chairman; he cut a $6M check. The second investor was Benchmark Capital, the esteemed venture firm. This is where things get tricky. The partners from Benchmark tried to cut Marc out of the deal. They were investing $15M and didn’t want to play nice with other investors. But Ben Horowitz was loyal to Marc Andreessen. Once Benchmark realized Marc wasn’t going anywhere, they conceded. To seal the deal, Ben, Marc, and Loudcloud execs visited the Benchmark office. One of the Benchmark partners started berating Ben, claiming he needed to get a real CEO. Ben was humiliated in front of the team that looked up to him. Him and Marc would never forget how Benchmark made them feel. The beef would only get stronger with time. Andreessen and Horowitz vowed to paint Silicon Valley red with Benchmark blood. And they had a good idea on how to do that. Horowitz sold Opsware (fka Loudcloud) to HP for $1.6B in 2007. Ben and Marc started angel investing into startups more heavily. Their portfolio expanded into thirty-six companies before launching a16z in 2009. When launching a company, founders think deeply about differentiation. How are we going to do this differently from our competitors? Are we able to use a wedge to open the door to other parts of the market? Can we eventually monopolize? Andreessen Horowitz was more of a startup than a venture firm. Their pitch was to flip the traditional venture model on its head. Instead of replacing founders like Benchmark, a16z would champion founders. Both investors had experience building billion dollar companies and could coach others. In addition, a16z would give founders connections to customers, media, and new hires. This would be paid for by using a portion of the management fees each year. Which meant that large fund sizes were a necessity to build out the “platform team”. In June 2009, a16z announced a $300M Fund I. With the new money, the firm built an in-house platform team to work for their startups full time. Another unique aspect of raising $300M right after the GFC is they could pay any price needed. a16z was handing out some of the highest valuations the venture market had seen in years. Obviously, this ended up working out for them… But at the time, it looked foolish. a16z invested in companies at any stage, from seed to growth rounds. They could be found in every area of tech investing, from a to z.

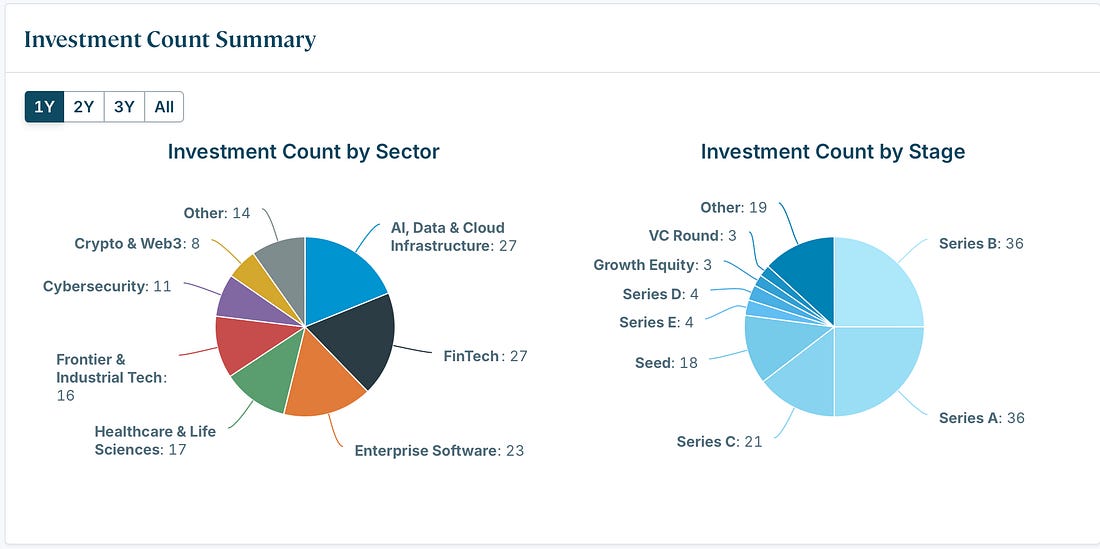

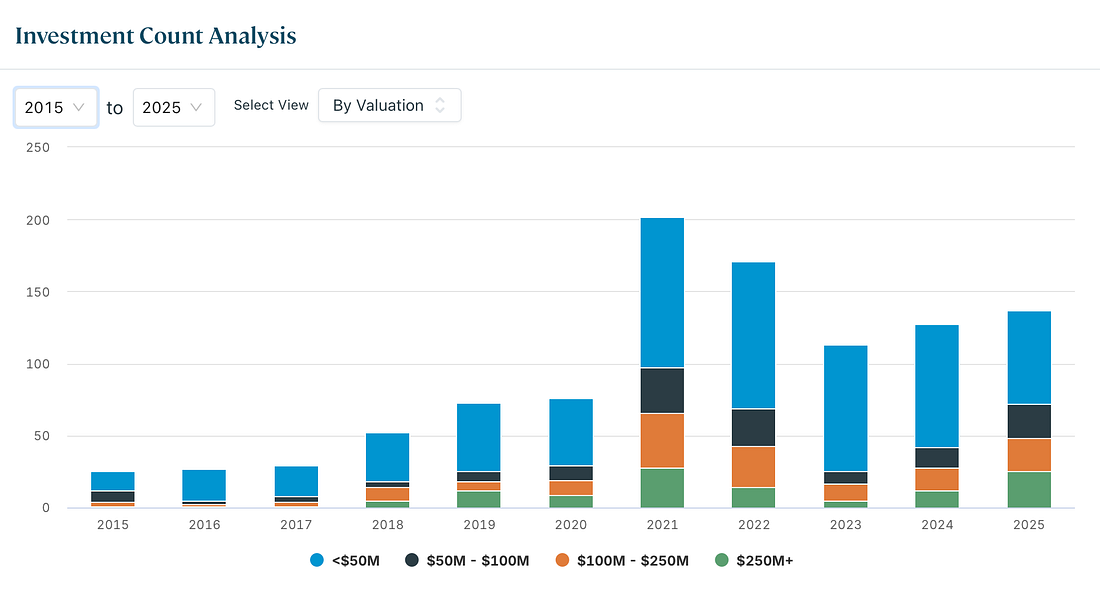

In September 2009, a16z invested $50M into Skype. The check amounted to more than 16.7% of the $300M, probably closer to 21% after deducting management fees. This was a highly concentrated bet very early on in the firm’s life - it was not, by any means, a typical investment. Andreessen was familiar with Skype because he was on eBay’s board of directors, and eBay bought Skype in 2005. After a few years, it became apparent that eBay was not going to succeed in properly integrating Skype’s technology into its core offerings, so it explored a sale, and Silver Lake, a tech-focused buyout firm, was the most interested party. Skype’s founders were vehemently opposed to the idea of joining Silver Lake’s portfolio, and they even took legal action to prevent the deal from going through, suing Silver Lake and making the situation even messier for eBay. In the midst of this chaos, Marc Andreessen saw opportunity. From a technical standpoint, Marc knew that Skype’s software could replace the hardware behind communication. Traditional voice calls relied on heavy infrastructure consisting of routers, gateways, and central switches connected by copper and fiber. Skype realized if computers could share music files, they could also share voice packets, and they set out to build a peer-to-peer network of user computers, where every computer acted as both a client, for receiving calls, and a node, for routing calls. This meant call traffic flowed through the computers and not through expensive, physical data centers. Marc used his software optimist persona to coax the founders into dropping their lawsuits and allowing both Silver Lake and a16z to invest in the company, while giving the founders 14% of their company back. eBay sold 65% of Skype to Silver Lake, a16z, and the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board at a $2.75B price. For context, in 2009, Skype generated roughly $700M in revenue. Although a16z’s $50M check was a drop in the bucket compared to the $1B+ Silver Lake put in, Marc Andreessen was an extremely active investor, and he leveraged his network to help replace 29 of the top 30 managers at Skype in an effort to restore order to the organization. Andreessen also brought Facebook to the table (he was an early investor in Zuckerberg’s project), striking a partnership that would allow Facebook users to chat with one another using Skype’s technology. The deal was instrumental in growing Skype’s user base from 400M pre-deal to 600M in just a year, a 50% increase. In 2011, Microsoft bought Skype at a $8.5B price tag, and a16z tripled their $50M investment in just 1.5 years, generating $100M in profit. This early foray into later stage investing was foreshadowing for what a16z was going to become. Traditional venture wisdom says a 3x return on capital is to be shunned; real venture capitalists aim for at least 50x or bust. All of that makes sense if you’re underwriting riskier situations and allocating 3% of total fund size to each startup initially. When you’re making a growth investment and putting more than a fifth of investable capital to work, a 3x return returns half of the fund size in cash. It’s the equivalent of a 20x+ exit on a smaller investment. And a16z actually added value to their portfolio company through the Facebook partnership and management hires. Andreessen wasn’t just another venture capitalist, he was a tech-centric activist investor. The first a16z fund ranked in the top 5% of venture funds within the 2009 cohort. Internal rate of return eclipsed 44% after fees, nearly three times higher than the S&P 500 during the same timeframe. What I didn’t mention earlier is that almost right after raising a $300M fund in 2009, a16z raised another $650M in 2010. There’s a lot to unpack here: (a) very few funds raise two flagships (the core fund) in back to back years, (b) even less first time funds - probably none outside of a16z - are able to raise their second fund a year after their first, and (c) the second fund was twice as large as the first. Limited partners were not doubling down based on performance, this wasn’t a hedge fund where performance could be accurately measured after just one year of operations, a venture fund takes quite a few years before meaningful signals emerge. Also, this was fresh off the Great Financial Crisis. Most firms were raising new funds every four years or so. Everyone else in the venture capital ecosystem - investors, reporters, limited partners from other funds - started to notice Andreessen Horowitz, and not in a good way. More of a “who are these guys” vibe. Nowadays, the fundraising cadence for tier one firms - think Sequoia, General Catalyst, Thrive - has compressed to a little under two years between each vintage. For everyone else, the timeline is slower, especially for newer managers without impressive track records. The reason a16z was able to raise so much money in such a short period of time is because they were great storytellers with a very unique offering and a relevant track record. While other fund managers agreed to play the same game - back founders at standard valuations, replace founders when a professional CEO was needed, stick to certain stages and sectors - a16z decided to bring the same level of innovation from Netscape and Opsware to venture capital. They wanted to break the doors down and change the laws entirely. A platform team was never heard of before, but Marc and Ben gave up the millions they would have made on salaries through management fees to finance an in-house consulting team for their founders to help them succeed. No one else had thought to do this. Only an outsider could see how comfortable venture capitalists were getting and think to disrupt the model. Limited partners had never heard a story like this; it was always we’re going to invest in this sector at the Series A stage or some variant of that same schtick. We’re going to give up our salaries to treat founders like movie stars with a full-blown supporting cast, we need to invest across sectors because there is so much opportunity in technology, and we have to raise a billion in two years to win the arms race - these guys were aliens. It also helped that they had already invested $10M in an angel portfolio that included Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter. And they founded two multi-billion dollar companies themselves. When Ben and Marc pitched a16z, allocators awoke from their recession-induced slumber and opened the checkbooks. Pace-wise, a16z was investing in a lot of companies. 76 in 2012. 97 in 2013. It makes sense, when you consider the absolute lack of restrictions in their thesis. Basically, the only thing they weren’t doing was buying stock in public tech companies. Other venture capital firms began to despise them. They weren’t just new guys saying that the old guys were doing it wrong, they were new guys saying the old guys were doing it wrong while raising billion dollar funds, starving the old guys, and tweeting about it. a16z is probably the firm most directly responsible for wiping out the middle ground in venture capital. Nowadays it’s either go big with billion dollar funds and large investment teams plus support staff or go small with a tight partnership - in some cases, just a solo investor. Management fees saw compression because a16z decided they would use theirs to gain a competitive advantage, not for short term delight. This year, a16z’s core fund did 135 deals (144 in the last twelve months). The fund does the vast majority of their work in the Series A and B stages, roughly 50% of deals to be precise. Thanks to Caplight, we are able to go into granular detail on the firm’s current focus. A couple of insights here: a16z did more $250M+ valuation deals this year than ever before (save 2021).

a16z doesn’t do a lot of seed.

No coherent themes emerge from their portfolio.

The hidden downside of having a16z lead your seed round.

The more I think about a16z as a hedge fund, the more their model makes sense. As mentioned earlier, that Skype deal was foreshadowing. Getting a 100x return on a $10M check is cool but the probability is low. Getting a 10x return on a $100M check is much higher probability, especially if you know the ins and outs of said asset and can add strategic value like Marc did with Skype. So why not do both when other venture investors are focused on the one? The strategy has returned $25B to limited partners and changed the way an entire industry works. Databricks is not a late stage company with little upside left - it’s a proven machine with the potential to flip $2B into $3B and return a fund in the process. You can talk about reduced IRR for all it matters, we are printing cash on lower risk plays, and still finding a couple winners on the early side. Andreessen Horowitz opened a can of worms that the largest venture capital firms have more recently started to experiment with. There are no longer boundaries - only opportunities. Josh Kushner’s Thrive Capital launched Thrive Holdings earlier this year, a permanent capital vehicle dedicated to investing in, acquiring, and operating businesses for the long term. The primary value add is layering AI on top of legacy industries like accounting, IT, and healthcare. One of their early investments is Crete PA, an accounting platform that plans to invest $500M into acquiring accounting firms and then infusing AI into workflows to improve margins. Crete has over $300M in annual revenue and has acquired more than 20 accounting businesses, with a total of 900 employees. Thrive Holdings also teamed up with ZBS Partners to deploy $100M into Shield Technology Partners, an IT roll-up platform that has acquired four managed service providers, with the intention of using AI to enhance operations. General Catalyst is riding the same wave. GC launched Health Assurance Transformation Company (HATCo) in early 2024 to acquire and operate a healthcare system for a long term timeframe. In October 2025, their deal to acquire Summa Health closed for a total price of $515M after approval from Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost. GC will also invest an additional $500M+ for long term capital funding and strategic investment. Summa Health is based in Akron, Ohio, and with the acquisition, shifted from a nonprofit structure to a taxed subsidiary. The healthcare system reported revenue of ~$2B in 2024, with an operating loss of $8M. It employs 8,500 people across two acute care hospitals, 15 community medical centers, a rehab hospital, a health insurance arm, and various research arms. This is a full scale big boy buyout that reads more like a KKR transaction than General Catalyst investment. Artificial intelligence is bridging the gap between smaller ticket venture scale investments and blockbuster buyouts - instead of doling out $20M so a founder can build artificial intelligence software to sell to hospitals that have long sales cycles and misaligned incentives, the largest venture capital funds are deciding to buy the hospitals themselves, which allows them to raise more money and eliminate barriers to tech adoption. Only time will tell whether or not these moves pay off from a returns standpoint; owning and operating is fundamentally different from investing and advising, and not every boring industry AI rollup will be a win. How long does it take to build things? The answer isn’t black and white. One might say Marc Andreessen started a16z in 2009 when he launched the fund publicly and finished raising money from limited partners. Another might say he started in 1999 when Benchmark made an enemy out of Marc and Ben, and the initial seeds for a new type of venture fund were planted in his mind. Yet another could argue that Marc Andreessen has been building a16z his whole life: from his quiet childhood in Wisconsin to his bachelor’s degree at UIUC to building Netscape with Jim Clark, so on and so forth. At each point in his life he was being formed for the next adventure, and every lesson learned translated into a new pursuit. Even after a16z created a series of successful funds, he was still building as if he had never won. Building is not a linear process where you go from 0 to 1 and the game ends then everyone goes home happily ever after. It’s endlessly continuous and all-encompassing; every moment of your life you are being created anew like a newborn in his mother’s womb. Building never ends Appendix:good things travel quietly. share mainstreet media with someone who moves like you do. |

Selasa, 16 Desember 2025

Andreessen Horowitz II.

Langganan:

Posting Komentar (Atom)

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar