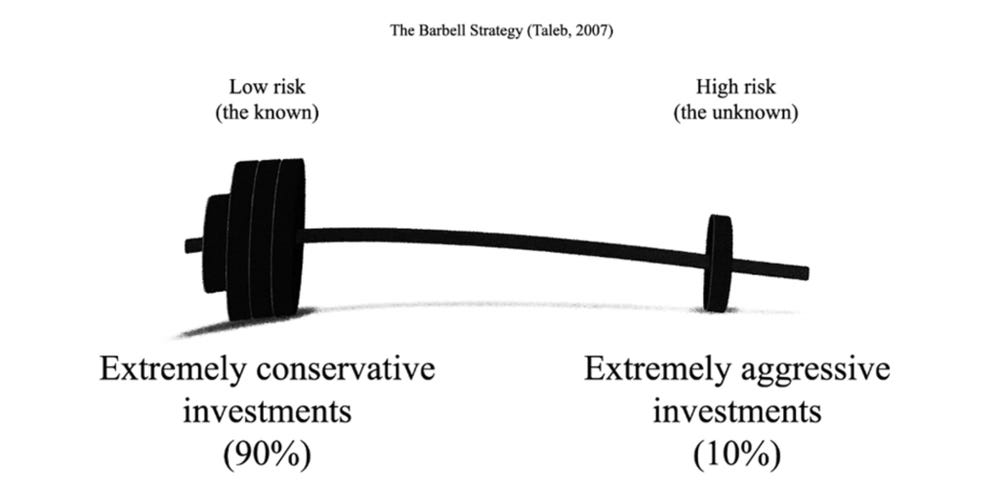

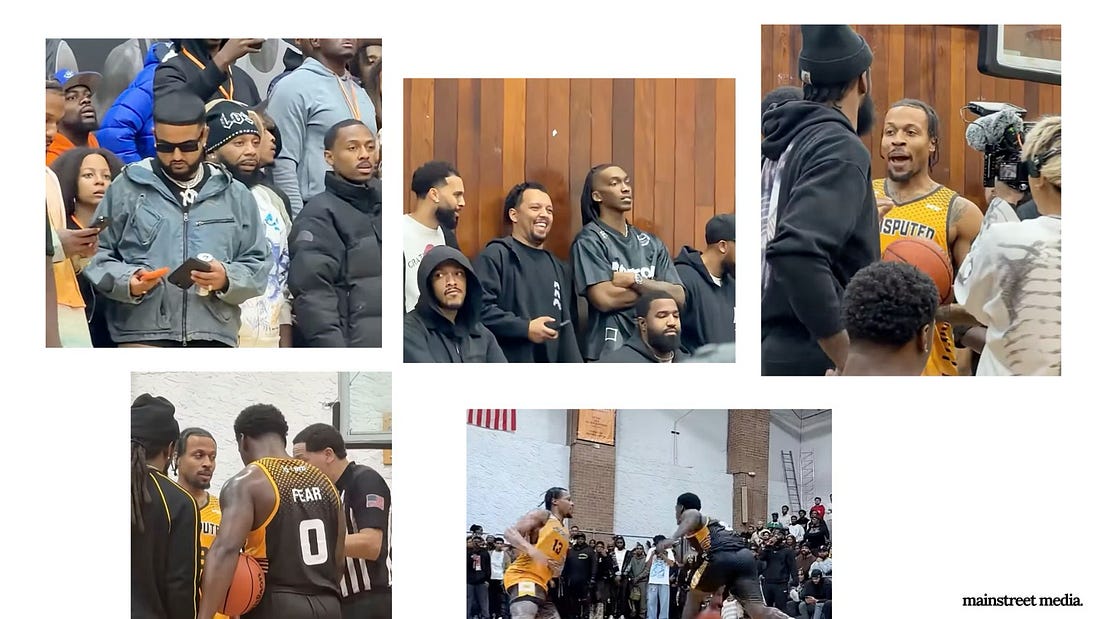

The older brother-younger brother rivalry is an archetype as old as time. Cain and Abel. Mufasa and Scar. The Prodigal son and his obedient brother. Despite the shared kinship, history highlights that the younger brother’s success often sparks jealousy in the older brother. But this isn’t always the case. The older brother can sometimes pave the way for the younger brother to chase greatness through leading by example. Think Obi-Wan and Luke Skywalker. This latter archetype has been the story of sports as an asset class. The number of emerging leagues, and thus capital flowing into them, has exponentially increased in recent years. Major League Pickleball. Tomorrow’s Golf League. Unrivaled. Premier Lacrosse League. United Football League. And many more. Even youth sports is seeing an unprecedented level of commercialization due to a surge of investor interest. But one cannot discuss the younger emerging leagues without first giving respect to the older brother: the Fantastic Four of American sports. The growth these four leagues have experienced over the past few decades is the main reason why the aforementioned emerging leagues can even exist in the first place. Institutional capital has bankrolled these emerging leagues but had long been prohibited from ever getting involved with the industry titans. Until a fortuitous day in October of 2019. One man in particular had been patiently waiting for this moment. Ian Charles did not come from the world of sports and in fact didn’t even watch sports growing up. He sometimes references being accosted for mispronouncing well known sports players or franchises. Rather, his background was in private markets. He initially wanted to be a physics professor and began studying the hard sciences at Texas Christian. This would change after he saw his friend’s finance homework and teased him about how easy the math was. His friend agreed and shot back, “Yeah, and I’m still going to make more money than you.” So Charles left behind the physics pursuit and shifted his eyes towards markets. He dove in headfirst by founding a software business and beginning the famous 0 to 1 journey. He’d seen the typical process founders go through: come up with an idea, pitch investors, raise money, and deploy the capital to chase growth at all costs. But unfortunately for him, the “raise money” part wasn’t exactly successful. To figure out where he went wrong, he began a deep dive into private markets, specifically private equity and venture capital. He figured if he spent time learning the intricacies of the market, he would understand why he wasn’t able to raise money and thus fix his errors. In addition to scouring every information platform possible, he began interviewing anyone in the VC and PE industry he could get in contact with and began building meaningful connections. Interestingly enough, the company he started didn’t dissolve after failing to raise outside capital; he eventually moved on to other pursuits while the two people he brought on bootstrapped the company for many years and are still in business today. This network enabled him to land a private equity job right after graduating from TCU before moving on to work at Cogent, a firm specializing in secondary advisory work. The company was founded in 2002 and quickly built the reputation as the go-to platform for secondary transactions, executing 55 deals valued at $11B in 2014 before being acquired by Greenhill Partners the following year. “If you wanted to sell secondaries in an intelligent way, we were literally the only firm to hire…we changed the cost of liquidity forever because the secondary market wasn’t that deep at the time but we helped increase the perception of liquidity that has greatly aided in the allocation to private markets.” After all, as a prospective LP in a notoriously illiquid asset class, the more confident you are that you can access liquidity at some point, the more likely you are to allocate capital. Charles then moved to Landmark Partners, another secondaries firm that was also later acquired by a larger company, this time Ares Management in 2021. During these stops, Charles acquired an expertise of private markets and alternative assets, specifically in deal origination and data analysis. He had begun to understand all of the alternative assets, but there was one in particular that was unlike the other. Sports. Specifically the major four sports leagues. He didn’t work with sports assets much during his stints at the secondaries firms, but the more he looked into it on his own time, the more he realized how unique it was. He quickly realized its most distinctive attribute was its anti-cyclical nature, as its performance is essentially uncorrelated with the broader macro environment. This is a trait that venture capital, private equity, real estate, nor any other major alternative asset could boast of. In fact, along with education and healthcare, it is the only industry / asset class that has experienced a compounded 3-year revenue growth of more than 6% over the past few decades. In addition to expanding margins and comparable returns to both private and public assets in expansionary times, sports franchises easily outperforms these assets in contractionary periods. For instance, during 2008 and 2009, each major sports league experienced notable growth in ticket revenue, contradicting the theory that lower discretionary spending from consumers due to a recession would naturally lead to decreased ticket sales. Another unique aspect of sports assets is that the franchises own a proportional amount of equity in its respective league that has its own revenue channels outside of the teams that includes domestic and international media rights deals, data sales, partnerships, and more. These deals are typically long-term contracts with escalators, thus, according to Charles, giving sports LPs access to something of “an investment-grade bond with growth” that is theoretically independent of the asset itself. But as we know, sports franchises were institutional investors’ forbidden fruit in the garden of private markets up until 2019. The MLB ruled that these institutions could now own a minority stake in teams, and the other leagues slowly followed suit. Charles quickly captured the opportunity and established Arctos in the same year. Charles brought his expertise in private markets, capital formation, and data to the table and brought on a few people (add) who specialized in sports management and operations. The S-tier team, promising asset class, and opportune timing seemed to be a home-run formula for fundraising, but the company inevitably ran into friction. Many were hesitant to commit, as the MLB was the only league to open up access and it wasn’t exactly obvious as to when / if the others would do the same. Because of this, many prospective LPs chose to sit on the sidelines. But a select few saw the opportunity and jumped at it, allowing the firm to raise $2B for their first fund. When analyzing why leagues had historically prevented institutions from being investors, it mainly came down to two words: control and leverage. Private equity firms are the most likely suitors for these franchises because of their size due to their high debt to equity ratio. They also notoriously aim to control their assets so that they have an active role in their “value creation methods.” Leagues understand this and thus wanted to exclude them from ownership, as the last thing they want is these institutions saddling teams with debt and usurping the decision making power. Taking on a significant load of debt is heavily discouraged by the major leagues, as a team’s financial insolvency due to inability to make interest payments can have a cascading effect on the rest of the league. Because of this, the average maximum allowable LTV hovers around 15%. With this in mind, it almost seems like a private equity firm like Arctos wouldn’t mesh well with the criteria. However, Charles’s background isn’t executing the textbook leveraged buyouts but rather helping investors access liquidity. This means he would not seek to alter the company’s foundations because his background was in minority stakes not in control stakes. Keeping his secondaries hat on, he saw a very similar situation he identified a decade or so at Cogent in which there were a lot of existing investors that wanted access to liquidity but had no well to draw from. Combining the opportunity to invest in a unique asset class, teams’ inability to take on debt, and a lack of liquidity for sports investments, Arctos kills three birds with one stone, specializing in deploying LP’s capital to sports assets, providing teams with no-strings-attached growth capital, and offering liquidity to current franchise investors. The powerful three-in-one. It became very obvious very quickly that Arctos was building something special. KKR took notice and recently acquired the firm for $1B. When did everyone start using the phrase “barbell strategy”? Was it purely Nassim Taleb’s doing? Taleb is an investor famous for making truckloads of money as a trader at First Boston during the 1987 crash, also known as Black Monday. On Black Monday, Taleb took out a long position on the Eurodollar through call options, which cost pennies on the dollar, and later that same day, he sold the options for a dollar each, pocketing more than a pretty penny in the process, around $35 million to be exact. Taleb went on to found a hedge fund, Empirica, that did well for a short period of time, but closed due to periods of low volatility. His strategy was dependent on large, black swan events that others were not pricing in. Like Black Monday or, more recently, COVID-19. Therefore, extended periods of low volatility were no fun for his fund. Taleb described his investment framework, detailed in one of his famous books, Fooled by Randomness, as barbell strategy, where most of the portfolio is in high quality, safe assets with low-risk returns, and a smaller sleeve of capital, think 10-20%, is in ultra high-risk, high-reward ventures, like out of the money call options trading for pennies on the dollar. Taleb likely used the name barbell because of his love for weightlifting. Today, the phrase is abused by far too many people. A New York socialite uses barbell strategy to explain why she eats kale caesar salad six days of the week before binging on eggs benedict and mimosas on the seventh. An NBA data analyst uses barbell strategy to justify his recommendation that players only shoot three pointers and layups. A venture capitalist in Menlo Park uses barbell strategy to rationalize only investing in serial entrepreneurs or college dropouts. And today, I will shamelessly clothe myself in the comforting linens of hypocrisy, and use barbell strategy to push my agenda on sports investing forward. The Arctos investment mandate was strict and unforgiving: blue-chip or die. Golden State Warriors, Sacramento Kings, Philadelphia Sixers, Washington Wizards, Boston Red Sox, LA Dodgers, Aston Martin F1, the list continues. Even within the “Big Four” landscape, the firm selected for teams that were either built for scale, or mistakenly undervalued. Eventually, the firm made a number of “emerging league” investments, but let’s set that aside for now. If the Arctos way represents the conservative stack of plates on the left side of our sports investment barbell, what is the aggressive, singular plate on the right? One might say Major League Pickleball. Another Unrivaled, the new women’s basketball league. Yet another, Major League Cricket, or Premier Padel, or Baller League, which features creators instead of professional athletes. Not enough. These leagues were created with institutional adoption in mind. Investors, ranging from venture capitalists to buyout moguls, have backed these leagues from day one, in hopes of cashing out amidst record levels of capital interest in sports. To find out where the real emerging leagues live, we must look beyond what the mainstream media puts on our plates. We must look in the cracks and crevices where investors are scared to visit. If you walked into the wrong basketball gym in New York on November 8th you would have seen it. What looked like a sold-out high school basketball game in the city was actually something far more nefarious. In one section of the gym, you would spot one of Canada’s most famous rappers, Nav, checking one of his two phones waiting for the festivities to start. Red Bull in the other hand. Local celebrities and corner boys alike packed the gym like sardines as the crowd waited in anticipation. Left and right, everyone was putting their money down on who would come out alive. Thousands of dollars at a time. This was the modern equivalent of Casanova’s underground fight rings in Brooklyn. And they started playing basketball. Nasir Core, a 29-year-old guard in Ice Cube’s Big3 league, squared off against Isaiah Briscoe, a 29-year-old guard who previously played at Kentucky alongside De’Aaron Fox and Bam Adebayo, before bouncing back and forth between the NBA’s G-League and overseas basketball. The event was structured like a UFC fightcard, with Nasir versus Isaiah as the main event, and players like Jahvon Quinerly and Ty Lawson hopping into the one-on-one arena to fight for their lives. One-on-one basketball is not a replacement for traditional hoops, it’s a flavorful supplement. It’s my ego versus yours. Just three, four dribbles to create separation and score. Nowhere to hide. At its best, it brings the thrilling ups and downs of fighting sports in a basketball format. At its worst, it can turn into an unpalatable sport, a violent evening, you name it. There is no real infrastructure around this; different platforms exist on YouTube, namely Ballislife, The Next Chapter, and Off the Dribble, but there is no official league to capitalize on the moment. The space is messy and fragmented. Events like the NYC card got compromised by hotheaded fans with too much money on the line. Figuring out the right business model will also take some tinkering. Right now, the channels charge viewers to watch the highest demand matchups (like Isaiah vs. Nasir) on a pay-per-view basis. Keeping the best players locked in for the long term will be a struggle. Attracting marquee NBA talent won’t happen anytime soon. There are many question marks that must be addressed. Nonetheless, one-on-one basketball is where the highest-risk, highest reward emerging sports opportunity lies. If someone can create the “UFC for basketball”, that’s a sports platform worth buying into at the earliest stage. The pull is already there: at a Detroit event hosted by Off The Dribble, breakout rapper Babyface Ray made an appearance; at a Charlotte event hosted by The Next Chapter, Hornets standout Miles Bridges showed up; at an Indiana event hosted by The Next Chapter, Pacers player Obi Toppin and former NBA player Marquis Teague both joined. This is where the culture is headed. It’s much riskier than pickleball or padel. But I’ll put my money down and see who comes out on top. On the topic of basketball, keep an eye out for Project B. Project B is a new global basketball league formed by former Facebook executive Grady Burnett and Skype co-founder Geoff Prentice, with the goal of introducing an F1 style international tour concept to professional basketball. At first glance, it seemed as if Project B was positioning itself as an Unrivaled competitor. Unrivaled is a 3v3 women’s basketball league founded to provide an alternative to WNBA players playing overseas in the offseason; they raised funding from a number of venture capitalists and celebrities, gave players equity in the league, and paid out higher average salaries than the WNBA, roughly $222,000 versus the WNBA’s $120,000. Project B, however, is reportedly handing out Birkin bags with $2,000,000 inside, nearly 10x Unrivaled’s average salary. The aggressive compensation structure has attracted a number of WNBA all-stars and former MVPs, including Nneka Ogwumike (10x all-star, 1x MVP, 1x champion), Alyssa Thomas (6x all-star), Jewell Lloyd (6x all-star, 3x champion), Jonquel Jones (5x all-star, 1x MVP, 1x Finals MVP, 1x champion), and a handful of other all-star level players. But disrupting the WNBA isn’t enough for these guys. Project B is trying to poach current high level NBA players as well. No announcements have been made as to which players they are signing on the men’s side. But be on the lookout for something later this year. Project B is an attempt to disrupt the NBA’s chokehold on basketball, backed by some of the largest technology companies in the world. The CEO of Google Ventures invested, a Managing Partner at CapitalG (Google’s growth equity fund) invested, a founding partner at Lightspeed invested, to name a few. We have to take a step back and look at the broader landscape to understand what’s happening. Technology companies are playing a bigger role in sports media rights packages. Amazon, YouTube, Apple. In the next cycle, more tech companies will join the fun, pricing out traditional media. At some point in the distant future, only tech companies will be able to afford media rights for the NBA/NFL. Burnett and Prentice, both tech executives who were early at Facebook and Skype, understand this perfectly. If they can dilute the NBA’s monopoly and build a product that appeals to their network of tech executives, the dividends will be endless. And if they succeed with basketball, it will not stop there. Every sport is up for grabs. The hardest part will be the product itself. Will fans care to watch after the novelty wears off? Certainly an international audience helps. But there’s a reason people tune in to the NBA Finals every year even if their team isn’t playing. There’s a reason the Super Bowl does the numbers it does. You can’t engineer that. for your eyes only. |

Selasa, 03 Februari 2026

Arctos Blitz.

Langganan:

Posting Komentar (Atom)

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar